When it

comes to climate change research, most studies bear bad news regarding the

looming, very real threat of a warming planet and the resulting devastation

that it will bring upon the Earth. But a new study, out Thursday in the journal

Science, offers a sliver of hope for the world: A group of researchers based in

Switzerland, Italy, and France found that expanding forests, which sequester

carbon dioxide from the atmosphere, could seriously make up for humans’ toxic

carbon emissions.

In 2018, the

United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, the world’s foremost

authority on climate, estimated that we’d need to plant 1 billion hectares of

forest by 2050 to keep the globe from warming a full 1.5 degrees Celsiusover

pre-industrial levels. (One hectare is about twice the size of a football

field.) Not only is that “undoubtedly achievable,” according to the study’s

authors, but global tree restoration is “our most effective climate change

solution to date.”

In fact,

there’s space on the planet for an extra 900 million hectares of canopy cover,

the researchers found, which translates to storage for a whopping 205 gigatons

of carbon. To put that in perspective, humans emit about 10 gigatons of carbon

from burning fossil fuels every year, according to Richard Houghton, a senior

scientist at the Woods Hole Research Center, who was not involved with the

study. And overall, there are now about 850 gigatons of carbon in the

atmosphere; a tree-planting effort on that scale could, in theory, cut carbon

by about 25 percent, according to the authors.

In addition

to that, Houghton says, trees are relatively cheap carbon consumers. As he put

it, “There are technologies people are working on to take carbon dioxide out of

the air. And trees do it — for nothing.”

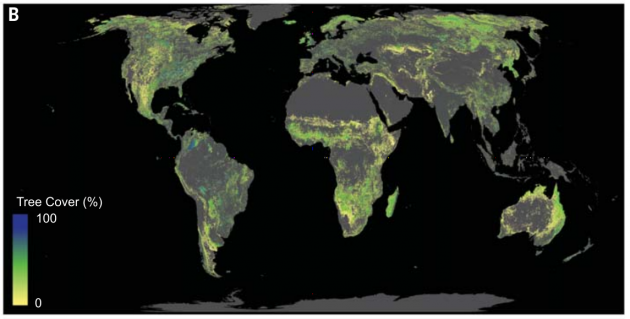

To make this

bold prediction, the researchers identified what tree cover looks like in

nearly 80,000 half-hectare plots in existing forests. They then used that data

to map how much canopy cover would be possible in other regions — excluding

urban or agricultural land — depending on the area’s topography, climate,

precipitation levels, and other environmental variables. The result revealed

where trees might grow outside of existing forests.

“We know a

single tree can capture a lot of carbon. What we don’t know is how many trees

the planet can support,” says Jean-François Bastin, an ecologist and postdoc at

ETH-Zürich, a university in Zürich, Switzerland, and the study’s lead author,

adding, “This gives us an idea.”

They found

that all that tree-planting potential isn’t spaced evenly across the globe. Six

countries, in fact, hold more than half of the world’s area for potential tree

restoration (in this order): Russia, the United States, Canada, Australia,

Brazil, and China. The United States alone has room for more than 100 million

hectares of additional tree cover — greater than the size of Texas.

The study,

however, has its limitations. For one, a global tree-planting effort is

somewhat impractical. As the authors write, “it remains unclear what proportion

of this land is public or privately owned, and so we cannot identify how much

land is truly available for restoration.” Rob Jackson, who chairs the Earth

System Science Department and Global Carbon Project at Stanford University and

was not involved with the study, agrees that forest management plays an

important role in the fight against climate change, but says the paper’s

finding that humans could reduce atmospheric carbon by 25 percent by planting

trees seemed “unrealistic,” and wondered what kinds of trees would be most

effective or how forest restoration may disrupt agriculture.

“Forests and

soils are the cheapest and fastest way to remove carbon from the atmosphere —

lots of really good opportunities there,” he said. “I get uneasy when we start

talking about managing billions of extra acres of land, with one goal in mind:

to store carbon.” Bastin, though, says the study is “about respecting the

natural ecosystem,” and not simply planting “100 percent tree cover.” He also

clarified that planting trees alone cannot fix climate change. The problem is

“related to the way we are living on the planet,” he says.

Caveats

aside, Houghton sees the study as a useful exercise in what’s possible. “[The

study] is setting the limits,” says Houghton. “It’s not telling us at all how

to implement it. That what our leaders have to think about.”

Comments

Post a Comment