Scientists

think they've identified a previously unknown form of neural communication that

self-propagates across brain tissue, and can leap wirelessly from neurons in

one section of brain tissue to another – even if they've been surgically

severed.

The

discovery offers some radical new insights about the way neurons might be talking

to one another, via a mysterious process unrelated to conventionally understood

mechanisms, such as synaptic transmission, axonal transport, and gap junction

connections.

"We

don't know yet the 'So what?' part of this discovery entirely," says

neural and biomedical engineer Dominique Durand from Case Western Reserve

University.

"But we

do know that this seems to be an entirely new form of communication in the

brain, so we are very excited about this."

Before this,

scientists already knew there was more to neural communication than the

above-mentioned connections that have been studied in detail, such as synaptic

transmission.

For example,

researchers have been aware for decades that the brain exhibits slow waves of

neural oscillations whose purpose we don't understand, but which appear in the

cortex and hippocampus when we sleep, and so are hypothesised to play a part in

memory consolidation.

"The

functional relevance of this input‐ and output‐decoupled slow network rhythm

remains a mystery," explains neuroscientist Clayton Dickinson from the

University of Alberta, who wasn't involved in the new research but has

discussed it in a perspective article.

"But

[it's] one that will probably be solved by an elucidation of both the cellular

and the inter‐cellular mechanisms giving rise to it in the first place."

To that end,

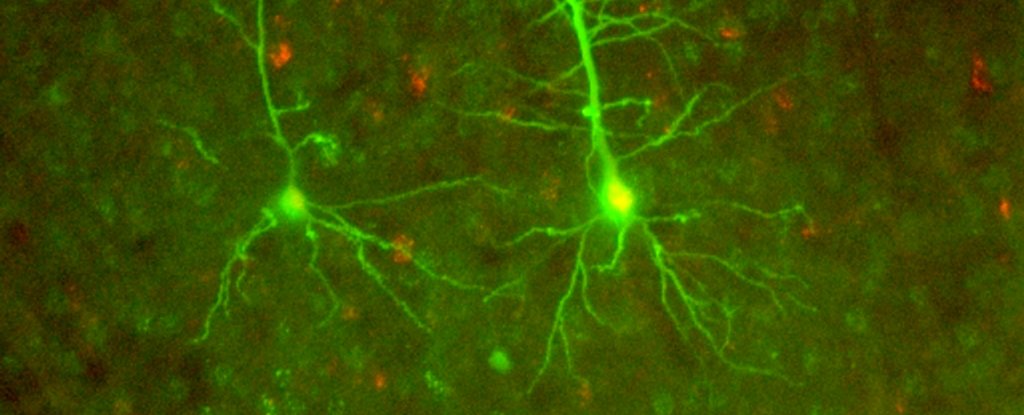

Durand and his team investigated slow periodic activity in vitro, studying the

brain waves in hippocampal slices extracted from decapitated mice.

What they

found was that slow periodic activity can generate electric fields which in

turn activate neighbouring cells, constituting a form of neural communication

without chemical synaptic transmission or gap junctions.

"We've

known about these waves for a long time, but no one knows their exact function

and no one believed they could spontaneously propagate," Durand says.

Learn more here.

Learn more here.

Comments

Post a Comment