You may have

witnessed this scene at work, while socializing with friends or over a holiday

dinner with extended family: Someone who has very little knowledge in a subject

claims to know a lot. That person might even boast about being an expert.

This

phenomenon has a name: the Dunning-Kruger effect. It's not a disease, syndrome

or mental illness; it is present in everybody to some extent, and it's been

around as long as human cognition, though only recently has it been studied and

documented in social psychology.

In their

1999 paper, published in the Journal of Personality and Social Psychology,

David Dunning and Justin Kruger put data to what has been known by philosophers

since Socrates, who supposedly said something along the lines of "the only

true wisdom is knowing you know nothing."

Charles

Darwin followed that up in 1871 with "ignorance more frequently begets

confidence than does knowledge."

Put simply,

incompetent people think they know more than they really do, and they tend to

be more boastful about it.

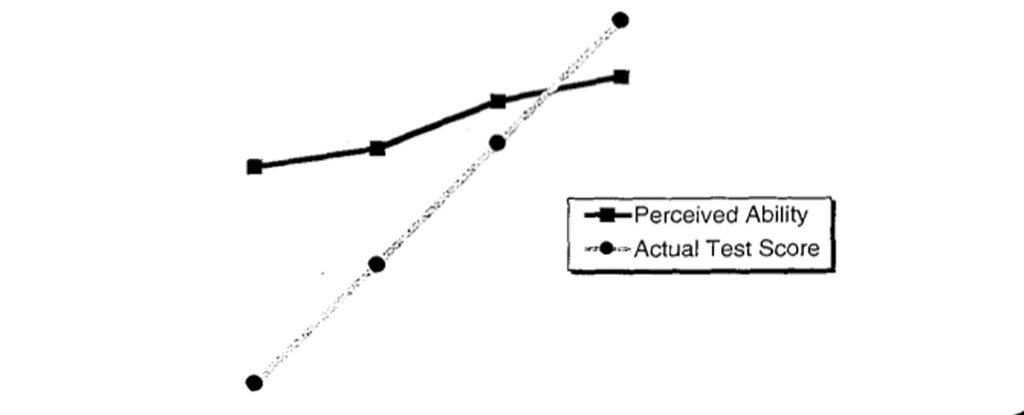

To test

Darwin's theory, the researchers quizzed people on several topics, such as

grammar, logical reasoning and humor. After each test, they asked the

participants how they thought they did. Specifically, participants were asked

how many of the other quiz-takers they beat.

Dunning was

shocked by the results, even though it confirmed his hypothesis. Time after

time, no matter the subject, the people who did poorly on the tests ranked

their competence much higher.

On average,

test takers who scored as low as the 10th percentile ranked themselves near the

70th percentile. Those least likely to know what they were talking about

believed they knew as much as the experts.

Dunning and

Kruger's results have been replicated in at least a dozen different domains:

math skills, wine tasting, chess, medical knowledge among surgeons and firearm

safety among hunters.

During the

election and in the months after the presidential inauguration, interest in the

Dunning-Kruger effect surged. Google searches for "dunning kruger"

peaked in May 2017, according to Google Trends, and has remained high since

then.

Attention

spent on the Dunning-Kruger Effect Wikipedia entry has skyrocketed sincelate2015.

There's also

"much more research activity" about the effect right now than

immediately after it was published, Dunning said. Typically, interest in a

research topic spikes in the five years following a groundbreaking study, then

fades.

"Obviously it has to do with Trump and the various treatments that people have given him," Dunning said, "So yeah, a lot of it is political. People trying to understand the other side. We have a massive rise in partisanship and it's become more vicious and extreme, so people are reaching for explanations."

Even though

President Trump's statements are rife with errors, falsehoods or inaccuracies,

he expresses great confidence in his aptitude.

He says he

does not read extensively because he solves problems "with very little

knowledge other than the knowledge I [already] had."

He has said

in interviews he doesn't read lengthy reports because "I already knowexactly what it is".

He has

"the best words" and cites his "high levels of

intelligence" in rejecting the scientific consensus on climate change.

Decades ago,

he said he could end the Cold War: "It would take an hour and a half to

learn everything there is to learn about missiles," Trump told The

Washington Post's Lois Romano over dinner in 1984. "I think I know most of

it anyway."

"Donald Trump has been overestimating his knowledge for decades," said Brendan Nyhan, a political scientist at the University of Michigan. "It's not surprising that he would continue that pattern into the White House."

Dunning-Kruger

"offers an explanation for a kind of hubris," said Steven Sloman, a

cognitive psychologist at Brown University.

"The

fact is, that's Trump in a nutshell. He's a man with zero political skill who

has no idea he has zero political skill. And it's given him extreme

confidence."

Sloman

thinks the Dunning-Kruger effect has become popular outside of the research

world because it is a simple phenomenon that could apply to all of us. And, he

said, people are desperate to understand what's going on in the world.

Many people

"cannot wrap their minds around the rise of Trump," Sloman said.

"He's

exactly the opposite of everything we value in a politician, and he's the exact

opposite of what we thought Americans valued." Some of these people are

eager to find something scientific to explain him.

Whether

people want to understand "the other side" or they're just looking

for an epithet, the Dunning-Kruger effect works as both, Dunning said, which he

believes explains the rise of interest.

The

ramifications of the Dunning-Kruger effect are usually harmless. If you've ever

felt confident answering questions on an exam, only to have the teacher mark

them incorrect, you have firsthand experience with Dunning-Kruger.

On the other

end of the spectrum, the effect can be deadly. In 2017, former neurosurgeon

Christopher Duntsch was sentenced to life in prison for maiming several

patients.

"His performance was pathetic," one co-surgeon wrote about Duntsch after a botched spinal surgery, according to the Texas Observer.

"He was functioning at a first- or second-year neurosurgical resident level but had no apparent insight into how bad his technique was."

Dunning says

the effect is particularly dangerous when someone with influence or the means

to do harm doesn't have anyone who can speak honestly about their mistakes.

He noted

several plane crashes that could have been avoided if crew had spoken up to an

overconfident pilot.

"You

get into a situation where people can be too deferential to the people in

charge," Dunning explained. "You have to have people around you that

are willing to tell you you're making an error."

What happens

when the incompetent are unwilling to admit they have shortcomings? Are they so

confident in their own perceived knowledge that they will reject the very idea

of improvement?

Not

surprisingly (though no less concerning), Dunning's follow-up research shows

the poorest performers are also the least likely to accept criticism or show

interest in self-improvement.

Comments

Post a Comment