Even the

tiniest organisms can make it to the big leagues. The number one fastest animal

movement in the world now belongs to an ant no bigger than the tip of your

finger.

Ominously

named the Dracula ant (Mystrium camillae), this minuscule species is shy and

elusive, a subterranean predator that enjoys sucking the blood from its own

hapless larvae in a practice fondly known as "nondestructive

cannibalism".

It's also

wicked fast. A new study has found that the jaws on this rare and mysterious

species can snap shut five thousand times quicker than the blink of an eye.

Using a

high-speed camera, scientists at the Smithsonian have now caught this

remarkable movement in action for the first time.

The

mechanism works sort of like a finger snap, except at a meteoric pace, one thousand

times faster than what human hands are capable of.

Pressing the

tips of its mandibles together, pressure between the ant's jaws begins to

build, until at last it reaches a breaking point, eventually releasing one of

the mandibles so it slides across the other.

From start

to finish, the action takes 0.000015 seconds, going from zero to around 320

km/h (198 mph) in a fraction of an instant.

This

particular species of Dracula ant has now taken the gold medal for the fastest

known animal appendage and the fastest known biological manoeuvre ever.

The genus

Mystrium has been called the "most mysterious group within the bizarre

Dracula ants", and scientists are still not sure why this cryptic ant has

evolved such special mandibles.

Although, in

the animal kingdom, when it comes to catching prey and avoiding predators,

speed is extremely important. Today, the fastest known movements are behaviours

based on hunting and defence, and these quick twitches are commonly observed in

arthropods like mantis shrimp, froghoppers and trap-jaw ants.

Among these

creatures, energy is stored up in the muscles and then released via a latch

that lets the energy loose through some sort of elastic spring. By

incorporating latches and springs, these animals are saved from overworking

their muscles, and this allows creatures like the Dracula ant to forage for

food and defend themselves against predators in the most efficient way

possible.

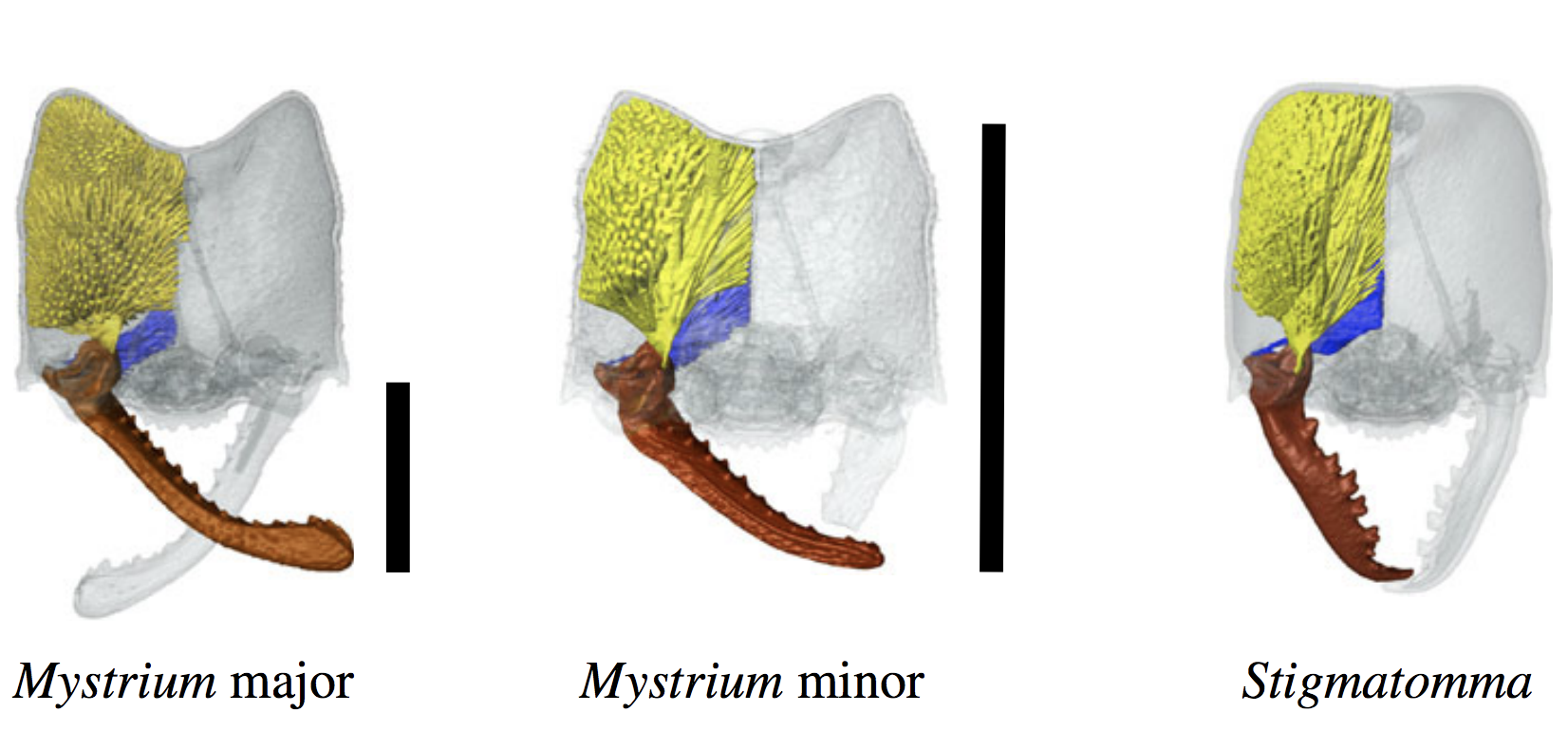

Even

compared to other trap-jaw ants, however, the Mystrium Dracula ant reigns

supreme. Currently, we know at least six lineages of ants that have similar

power-amplified mandibles, but the Mystrium camillae has a unique morphology

that makes it especially quick.

Unlike other

ants with trap-jaws, the mandibles on these fellas start from a closed position

and then slide across each other. What's more, the spring and latch mechanisms

that allow the jaw to slam closed are embedded within the mandible itself.

This unique

structure is probably what gives this genera such speed. In trap-jaw ants like

the Odontomachus and Myrmoteras genera - where the spring, latch and trigger

structures are separated - it takes three to sixty times longer for the jaws to

close. And even at peak velocity, this movement is still ten to twenty times

slower than what Mystrium camillae is capable of.

The authors

of the paper think that maybe these special jaws developed alongside this ant's

unique underground habitat - in the tropics of South East Asia and Australia -

where open jaws are not really an option.

"The

foraging and nesting habits of Mystrium are also restricted to confined tunnels

in logs and in the soil, and this may favour this type of amplification system

where the ant cannot open its jaws widely as seen in trap-jaw ants which

largely forage in open spaces," the authors propose.

But we still

can't be sure. These creatures are like buried treasure, and more research will

be needed if we want to know why they have developed such expeditious

trap-jaws.

This study

was published in the Royal Society Open Science.

Comments

Post a Comment